Creating Biodiversity By: Stacey Wildberger

February 2, 2017

Alternatives to Mosquito Control

April 24, 2017By: Stacey Wildberger

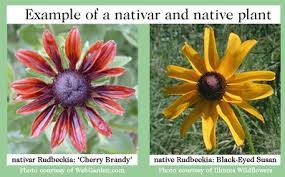

I have been writing about using natives in your backyard landscape and the benefits they provide to wildlife but what about the nativars we hear so much about and see in the local garden center? As you start adding to your gardens this spring it is important to understand what a native straight species plant is vs a nativar or cultivar of a native plant.

Nativars are cultivars of native plants that have been propagated for specific “desirable” traits. They are becoming increasingly popular as alternatives to native “straight species”. A native plant is a plant species that occurs naturally in a particular region, habitat, or ecosystem. A nativar is a result of artificial selection- its traits have been selected by humans for some particular need to improve on the natural. The colors, bloom size/ shape, and even their height have been altered for our gardens. While a native freely propagates or self sows in the wild and in your garden a nativar cannot propagate naturally.

What are the pros and cons of using nativars? While the characteristics that they are bred for- longer bloom times, variety of color and shapes, disease and pest resistance can offer enticing attributes to the home gardener but there are even more reasons to skip the nativar and just use the straight species natives. Let’s look at how wildlife is affected. Many of the traits that excited the home gardener are less appealing to our pollinator friends. Bees are looking for the purple color of Echinacea found on native purpurea (purple coneflower) not the manipulated yellow, orange, and pink blooms of the many nativar varieties we now have. Not to mention those changes in the shape of the bloom, often making pollen collection more difficult. The results of these changes are loss of quality in the pollen and nectar, diminished quantity, and inaccessibility.

Natives have many advantages over nativars including adaptation to local soil and climate, they are the preferred food for native insects, and they promote biodiversity, conservation, and stewardship of our natural world. On the other hand, nativars face many challenges such as a loss of genetic diversity, less adapted to local conditions, less likely to be pollinated and will not self sow.

A nativar may also be less hardy then their straight species counterparts or have different soil requirements making them less adaptable to local soils and climates. They are some examples of nativars attracting pollinators as well as a native species would: in particular, the Asclepsis tuberosa (milkweed) “hello yellow” and Monarda fistulosa (bee balm) “Claire Grace” are 2 examples. A key factor in keeping the pollinators interested is less manipulation. The more a species is altered, the less likely it will be to attract pollinators and benefit wildlife.

While the use of some nativars in our home garden is acceptable it is important we understand the diminished benefits to our local wildlife, in particular pollinators. Many times local nursery and garden centers do not carry the straight species of a plant and the only thing available is a nativar. Choosing the nativar over an alien species from another country is preferable. If you are working on restoration and conservation projects it is recommend that you choose the straight species of the native plant to replicate the natural ecosystem. While there is still much to learn about nativars and their effects on the natural world there is one thing we do understand –native plants have co-evolved with local fauna for centuries and have proven themselves to be beneficial.

If you goal is to preserve biodiversity in your backyard through preservation, restoration and to establish native plant communities your first choice should always be the straight species native plants.

Rick Darke and Doug Tellamy offer this definition of a native in their book A Living Landscape–“A plant or animal that has evolved in a given place over a period of time sufficient to develop complex and essential relationships with the physical environment and other organisms in a given ecological community”